What to expect from COP30

Introduction

This briefing is for key businesses and members of the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL) network to understand likely focus areas at the upcoming COP30 meetings in Belém, Brazil as part of the ongoing United Nations (UN) climate change negotiations.

For more details of CISL’s events and engagements please see the COP30 hub on our website.

Do the COPs matter?

The Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is the primary global meeting place and discussion forum for agreeing multilateral efforts to tackle climate change. The UNFCCC was agreed in Rio in 1992, and subsequently full meetings under the Convention have taken place roughly annually, giving rise to the numbered series of COPs. This process gave us major agreements like the Kyoto Protocol (agreed at COP3 in 1997) and the Paris Agreement (agreed at COP15 in 2015). While being a venue for talks between governments, the COPs have also increasingly recognised the contribution of other actors like businesses, civil society groups, local governments and more.

The negotiations have delivered progress in areas such as global commitments to cut emissions, reporting frameworks, climate adaptation and mobilising finance, but they have also faced criticism for the slow and repetitive nature of the talks and the inadequacy of the progress achieved. Criticisms have focused on the disproportionate influence of petrostates under the consensus-based decision-making of the talks,1 the role of fossil fuel lobbyists,2 lack of enforcement mechanisms3 and slow progress towards actual emissions reduction in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence on the need for rapid decarbonisation.4

This was emphasised by a call for “urgent reform of the UN climate talks” that was backed by more than 200 civil society groups during the 2025 Bonn meeting,5 calling for changes such as majority-based decision-making when consensus fails, and stronger accountability for corporate interests (a measure also supported by CISL through We Mean Business Coalition’s (WMBC’s) Business Call for Accountability6).

While far from perfect and while failing to deliver anything like the necessary progress, the negotiations have delivered where other multilateral processes have failed and are inclusive and credible, allowing a voice to otherwise marginalised countries.

CISL continues to engage with the COP process to advocate higher ambition and faster implementation alongside our partners; we believe it is critical that stakeholders including sustainability advocates and leading businesses continue to support the negotiations, building on our long history of influencing policymakers, convening key economic actors, and providing thought leadership on the imperative of a socially just low carbon transition.

The global context

COP30 will be taking place in a world quite different from even a year ago, with geopolitics becoming ever more polarised and volatile. Following developments including the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris Agreement7 and Brazil’s suspension of the widely hailed soy moratorium (that has excluded soybeans grown on deforested land from supply chains since 2006)8 just months before hosting COP, the world appears in many respects to be moving backwards rather than forwards in our global efforts to combat climate change.

However, this is not the full picture; at the same time the growth in deployment of renewables is rocketing, with three times the capacity expected to be added in the next five years compared to the last five.9 The International Court of Justice recently ruled that countries are legally required to protect and prevent harm to the environment, with potentially far-reaching consequences for climate litigation and other legal procedures around the world.10 And in the face of explicit repudiation of climate action from the US, it is powerful how few other countries have followed this change of tone.

The basic facts of the climate crisis have not changed, and in the face of the headwinds facing climate diplomats, the upcoming COP holds significant importance for the multilateral process on climate and the impact it can deliver as climate impacts become increasingly widespread and urgency grows.

From COP29 to 30

The core debate at COP29, just as at many COPs, was around mobilising climate finance. In order to support global action on climate change, developing countries argued that they needed resources from countries that have most significantly caused climate change to help them switch to a low carbon economy and cope with the impacts.

At COP29, the main outcome was a new target for mobilising this climate finance – the ‘New Collective Quantified Goal’ (NCQG). However, this agreement fell far short of what developing countries were arguing for (particularly around the issue of grants and concessionary finance vs. ‘investment’ as preferred by developed nations11) and what independent experts said was needed.12 The final figure for the NCQG of US$300 billion a year by 2035 was only agreed when it was also accompanied by a larger promise to seek to mobilise US$1.3 trillion per year for Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS).13

The level of ambition from countries on climate change was also under scrutiny at COP29, with updated national plans, known as Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs, due shortly after the conference. A notable moment arose when the UK came forward with a stronger 2035 climate target, demonstrating real leadership on the global stage (one of just a few Parties to do so during COP). In the lead-up, the UK Corporate Leaders Group (CLG UK) – in line with a global effort by the We Mean Business Coalition – had been actively advocating an ambitious and investible UK NDC through a co-ordinated campaign, helping to reinforce the case for strong national leadership.

Alongside the above, steps in areas such as carbon markets and national-level commitments from countries including Indonesia, Brazil and Mexico meant that although progress at COP29 was limited, it did provide a foundation on which the Brazilian COP30 presidency can build.

Read CISL’s full COP29 reaction.

CISL’s expectations for COP30

The Brazilian COP30 presidency is working hard to ensure that Belém is a success, trying new approaches to collective engagement such as the Action Agenda and Global Mutirão alongside core negotiating priorities around finance, renewables and adaptation among others. The talks are likely to benefit from momentum generated by Brazil’s G20 presidency in 2024 and current role as chair of the BRICS bloc in areas such as bioeconomy and domestic finance,14 even as the wider geopolitical issues are challenging.

One area where progress is hoped for is on cutting climate change causing emissions and transitioning to renewable energy. This takes forward the outcomes of the first ‘Global Stocktake’ (GST) of progress to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, which concluded in 2023. Those conclusions prompted a landmark pledge agreed by COP28 to transition away from fossil fuels. Further progress on this was pushed back to COP30 following a lack of consensus on the scope of the GST, with a group of LDCs among those arguing for finance to be the main focus of discussions, while others were keen for a broader scope encompassing areas such as greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and renewable technologies.15

On adaptation to climate impacts, countries are currently undergoing an exercise to develop indicators to assess progress on this. This list of no more than 100 globally applicable indicators is expected to be adopted in Belém, which will effectively operationalise the Global Goal on Adaptation agreed at COP29.16

Finance will continue to be a key theme, with a need to fill the gap between current climate finance pledges and the new finance goals (US$116 billion was delivered in 202217). The ‘Baku to Belém Roadmap’, a presidency-led initiative which will set out the process for scaling up climate finance to developing countries to US$1.3 trillion, is expected at COP30. 18 CISL’s Investment Leaders Group contributed to the consultation on this roadmap.

Additionally, negotiations under Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement – which concerns the realignment of financial flows with the 1.5oC goal – give space for countries to agree wider transformations of the financial system, such as financing mechanisms for renewables and limiting financing of coal for example. These negotiations are also due to conclude in Belém but have faced ongoing difficulties centred around different interpretations of the agreement.19

Given the location of COP30 in one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth, the interlinkages between nature and climate are likely to be more prominent in 2025 than at previous meetings. It is increasingly recognised that natural ecosystems play an essential role in both reducing the extent of climate change and coping with its impacts, and more and more voices are calling to align the UN climate talks with sister talks on biodiversity and desertification. Also drawing on the local context in Belém, the role of indigenous peoples and local communities in addressing climate change is likely to be highlighted, with an Indigenous People’s Circle already launched by the COP30 presidency.20

Finally, Brazil, as host and president of the talks, has identified COP30 as the “implementation COP”. Belém should be a key moment to ramp up ambition around emissions reduction. 2035 climate targets should have been submitted by countries, along with a review of progress on 2030 targets. These are likely to show that current plans are insufficient to meet global climate goals, and leading governments, businesses, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and activists can be expected to call for higher ambition and faster implementation ahead of the conference.

CISL has been working through our Corporate Leaders Groups (CLG) to support WMBC’s Call to Action for Ambitious and Investable NDCs, which lays out key asks to policymakers for NDCs that drive accelerated private sector investment in the net zero economy.21

The UK Corporate Leaders Group will be sending a delegation to Belém as an official sponsor of the UK Pavilion. The team will be continuing their engagement with the UK Government by convening businesses and advocating for stronger policy frameworks that accelerate the clean, green transition.

The Global Mutirão

One interesting proposal from the Brazilian presidency is the Global Mutirão approach: a call from the presidency for a collective, community-driven mobilisation to “build momentum around climate action and ambition, and to create the conditions for an inflection point in our climate fight”.22

Outlined in May 2025, this new and experimental approach seeks to inclusively co-create a global framework in which stakeholders at different levels and in diverse geographies will be encouraged to present ‘self-determined contributions’, serving as bottom-up action (as opposed to the top-down, government-led nature of NDCs). In line with COP30’s positioning as a key moment for implementation, the Mutirão focuses on getting on with the job of addressing climate change through concrete action; the presidency positions this as “taking responsibility for positive change, rather than just advocacy, demand, and expectation”.

While it remains to be seen exactly how this will impact the actual negotiations, placing a greater focus on community agency at the grassroots level is a new way of working for a COP presidency, and could lead to a greater focus on existing actions and evolving solutions rather than commitments and targets around planned future activity, as has become a feature of recent COPs. The presidency has also used the Mutirão approach as a lens through which to encourage the building of an “infrastructure of trust” ahead of the SB62 negotiations in Bonn.

Forming a key part of this approach, the COP30 Action Agenda places emphasis on bringing action by non-state actors much closer to the negotiations and focusing it on the implementation of the Global Stocktake (GST). This agenda is framed around six areas (or ‘axes of action’) that range from transitioning energy systems to transforming agriculture, with a total of 30 objectives sitting under these six axes. The intention is to leverage existing initiatives to accelerate and scale implementation while driving transparency, monitoring and accountability of existing and new pledges and initiatives.23 The presidency intends to invite all stakeholders to join ‘activation groups’ under each key objective.

ClimateWise, CISL’s insurance industry leadership group, has been invited to join Action Agenda Working Group Number 21 on ‘Finance for Adaptation’, and as part of this will contribute to case studies and the joint forward-looking plans of the group.

Fossil fuels, renewables and the Global Stocktake (GST)

Agreed at COP28 in 2023, the Global Stocktake (GST) is an agreed assessment of the collective progress made towards the goals of the Paris Agreement, with the outcomes informing countries and other stakeholders in their actions to tackle climate change.

GST paragraph 28 calls on Parties to accelerate efforts to triple renewable energy capacity globally by 2030, to double the global average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030, and to transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner.24

COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago has identified taking forward the recommendations of the GST as one of the presidency’s top three priorities for the 2025 talks.25

Energy transition in Latin America and the Caribbean

The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region is well placed to demonstrate leadership and ambition in support of this agenda. During the June 2025 UN Climate Week in Panama, Honduras joined the Powering Past Coal Alliance, an indication that LAC is moving irreversibly away from coal and is now a continent free of planned coal expansion projects, adding momentum to the Call to Action for No New Coal.26 Coal provided just 4 per cent of the region’s electricity in 2024.27

Elsewhere in the region, Chile generated 33 per cent of its electricity from renewables in 2024, while Colombia has announced 19 measures to remove regulatory obstacles that have been delaying the expansion of renewables.28 Mexico has announced over US$32 billion of public investment to expand and strengthen its grid to allow for the better integration of renewables, demonstrating both a recognition of the economic opportunities from the energy transition and a commitment to realising these through substantial, future-proofed infrastructure investment.

Despite promising indicators within the LAC region and more widely, there remains a need for policymakers to enable an accelerated energy transition by deploying a range of methods at their disposal.

The Ibero-American Business Network for Green Growth (IABN), convened by CISL, is launching a campaign in support of the goal of tripling renewables by 2030, calling for a just, inclusive and prosperous energy transition in Latin America and beyond in the run-up to COP30.

Specific asks of policymakers under this campaign include committing to fossil fuel phase-out while prioritising new investments in renewables; submitting robust NDCs reflecting and enabling these commitments through detailed sectoral plans; prioritising investment in grid infrastructure, energy storage and distribution systems; and working with businesses and communities to design and implement frameworks that promote community benefits and protect and enhance nature.*

While focused on the LAC region, these policy measures are among the tools governments around the world might be expected to implement in order to align their national activities with the outcomes of the GST, which recognises that existing efforts are insufficient and off-track to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and avert the worst impacts of climate change.

* Full statement to be published at Climate Week NYC in September 2025

Adaptation, and loss and damage

Adaptation to climate impacts is one issue expected to be front and centre during COP30; indeed, the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) was listed first among the areas of ‘special focus’ laid out by the presidency in their third letter. Extreme weather events alone have cost the global economy over US$2 trillion over the last decade.29 Alongside efforts to adapt and minimise costs like these, however, is a parallel ‘loss and damage’ agenda which seeks to address the unavoidable and already existing harms, particularly to the most vulnerable. Adaptation and loss and damage are distinct yet complementary pillars of a comprehensive climate response, and both will require focus and resourcing to make progress at COP30.30

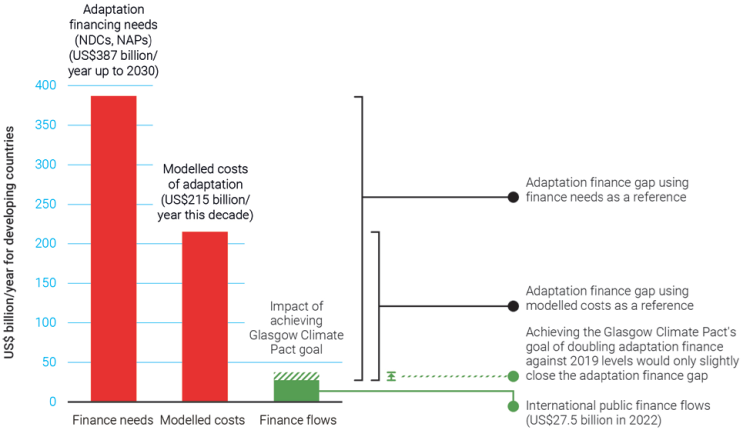

For the GGA, a final set of indicators to track progress towards the goal is expected to be adopted in Belém. This will effectively operationalise the GGA, giving countries and other stakeholders greater clarity on how the global goal will be achieved and, in theory, allowing action to ramp up in the effort to adapt to climate change. Financing plays a big role here; the adaptation finance gap is estimated at up to $387bn/year for developing countries this decade by (see figure below).31 At the same time, analysis by the World Resources Institute has shown that over a ten-year period (2014–24), for every US$1 invested in adaptation, over US$10.5 in benefits are yielded with average returns of 27 per cent for individual investments.32

The last time countries came to an agreement regarding adaptation finance was at COP26 in Glasgow, where developed countries were urged to double adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025. Notably, Parties did not specify a new adaptation finance target as part of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) at COP29, and therefore despite this need there will be no adaptation finance goal unless a new one is adopted at COP30, given the conclusion of the existing goal this year.

Loss and damage costs in developing countries are projected to reach US$400 billion per year by 2030, but when the loss and damage fund was launched at COP28 in Dubai (itself a major political achievement) countries pledged only US$700 million, or under 0.2 per cent of this amount.33 In 2025, developing countries will be looking for increased contributions to the Loss and Damage Fund set up to funnel funding to this area.

So far in 2025, negotiations around adaptation and loss and damage have shown some limited signs of progress. For example, clearer guidance was issued to experts developing indicators under the GGA that these should number no more than 100 (reduced from 489) and a timeline to complete the work ahead of COP30 was set out. Given differing views among countries on the means of implementation of the GGA (especially related to finance and national budgets), negotiations around adaptation have the potential to be difficult in the run-up to and at Belém.

Accountability for a just transition

A just transition involves ensuring that addressing climate change is an inclusive and socially just process that acknowledges historically marginalised voices and the needs of vulnerable groups. The COP30 presidency has identified it as another priority. Efforts such as the People’s Circle led by Brazil’s Minister for Indigenous Peoples, Sonia Guajajara, reflect this intent. It is important to the presidency that indigenous voices have a platform, as shown by their appointment of a Special Envoy for Indigenous Peoples. Given Brazil’s large indigenous communities, this theme is likely to run through many elements of the COP process in 2025. However, some concerns have been raised about the presidency’s engagement with indigenous representatives, with prominent indigenous leaders cautioning that current processes only amount to information-sharing rather than meaningful participation in decision-making.34

As for the actual negotiations, a Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) was launched at COP27, operationalised at COP28, and completed its first full year of work in 2024, including holding two dialogues and a high-level ministerial roundtable (in line with its mandated annual activities).35 However, the JTWP has struggled to make progress over the last few years, with Parties unable to resolve a number of differences, and with even a decision on the future scope and direction of the programme’s work not adopted. Discussions around just transition were among several that continued into the second week of COP29. While small steps forward were made in negotiations this year with a text containing strong messages around rights, equity and participation for the JTWP (and Parties showing a notable willingness to engage in constructive dialogue), the real negotiations are still ahead.36

Given the relatively limited progress so far, there is potential scope for making significant strides on the just transition agenda in Belém.

Integrating nature

Given the location of COP30 – Belém, the capital of Pará state, is the gateway to the lower Amazon region – it is perhaps unsurprising that the role of nature is attracting heightened focus for this round of talks. This should not be seen as a one-off result of this COP being held in a highly biodiverse region, however; the interlinkages between climate and nature, with each area being critical to the other, mean that this theme is expected to have a growing role in the climate conferences well beyond COP30. Additionally, from a regional perspective, COP16 (the ‘nature COP’ under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), one of the other three Rio conventions that sit alongside the UNFCCC) was held in Cali, Colombia in late 2024. The opportunity to elevate nature on the climate agenda as part of a regional mobilisation from one side of the Amazon basin to the other was supported by over 70 cross-sector leaders (including CISL) in an open letter to Presidents Petro of Colombia and Lula of Brazil during COP16.37

In recent years, calls have increasingly grown to better align the three Rio conventions (UNFCCC on climate, CBD on biodiversity, and UNCCD on desertification) in order to avoid treating interlinked systems as siloed issues and thereby potentially missing opportunities for more effective, joined-up policymaking. This was recognised in the final text of COP16, which invited countries to ‘strengthen synergies’ between conventions, though stronger wording and specific references to certain frameworks and agreements were notably removed from the text in the final hours of negotiations to reach consensus.38 More recently, at the UNFCCC negotiations in June 2025, informal consultations on synergies were held following a concerted push by the COP30 presidency, Colombia and others. It remains to be seen how this will be taken forward in Belém, but it is encouraging to see several Parties willing to take ownership of keeping this topic firmly on the agenda.

The Brazilian presidency has defined the COP30 Action Agenda, in which one of the six thematic areas is ‘Stewarding Forests, Oceans and Biodiversity’, demonstrating an explicit recognition of nature as a priority.39 As part of their NDC, the government of Brazil is exploring novel approaches to halt deforestation and promote forest recovery, such as a new concession model to transfer deforested land to private companies for reforestation and restoration, while businesses are following such signals by investing in initiatives to reduce deforestation.40 Other countries are likewise keen to support this agenda, with the UK government, for example, attempting to drive private finance into nature protection and restoration activities in line with international commitments and targets.41 Given that only 33 per cent of nature-related policies published since the Paris Agreement have allocated budgets, this push for nature finance is a key part of the puzzle and cannot be realised soon enough.42

Recognising this, perhaps the most significant nature-related initiative on the COP30 agenda is the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), the largest-ever funding mechanism for forests. The TFFF is a blended finance instrument seeking to mobilise US$125 billion from public and private sources, with the aim of providing a long-term source of finance for countries that keep their tropical forests standing. At an initial fixed rate of US$4 per hectare of forest per year, nations will receive payments based on performance, which will be discounted if deforestation or forest degradation increase.43 Spearheaded by the Brazilian government, the TFFF is planned to launch at COP30, and has significant potential to incentivise the protection and restoration of tropical forests.

For businesses and financial institutions wondering how they can play their part in driving momentum ahead of COP30, and advocating ambitious negotiating outcomes around nature in Belém, CISL partners WMBC and Business for Nature are producing an advocacy toolkit around the climate–nature nexus to be released before COP.

Who pays?

Finance has been a dominant theme at recent COPs, and Belém is likely to continue this trend. Though the US$300 billion goal agreed at COP29 fell significantly short of what many (particularly developing and vulnerable countries)44 were hoping for, the larger NCQG ambition of reaching US$1.3 trillion per year from public and private sources by 2035 is being taken forward by the ‘Baku to Belém Roadmap to $1.3T’. As mandated under this roadmap, throughout 2025 the COP29 and 30 presidencies have been exploring how to achieve this scale-up with an emphasis on grants, concessional and non-debt creating instruments, with a report on this process due by COP30.45 In preparation for the launch of the roadmap, the UNFCCC invited submissions from a range of stakeholders within the ecosystem to share their views. CISL contributed to this consultation process with key asks including the need to define clear pathways for finance mobilisation, leverage innovative financial structures, enhance the effectiveness of catalytic capital and strengthen risk management and guarantees.46

Depending on how these and other contributions materialise in the recommendations put to policymakers in Belém, and how they in turn move to progress key initiatives, this could have significant implications for financial institutions and the private sector as their role in contributing to the US$1.3 trillion target becomes clearer. However, multiple countries have expressed uncertainty on the process for developing the roadmap itself, the process for implementation, and how this relates to other initiatives such as the Circle of Finance Ministers, leaving the presidency with both a challenge and an opportunity when reporting progress and next steps on the roadmap in Belém.

Discussions around Article 2.1(c), which concerns aligning financial flows with the Paris Agreement, are facing calls to shift from dialogue to formal negotiations at COP30. This could involve measures such as developing an accounting framework to track financial flow alignment, tackling fossil fuel subsidies and defining targets and plans for governments, banks and corporations to re-align financial flows away from environmentally harmful activities.47 Discussions on this topic in Bonn revealed a lack of clarity on how work will progress around Article 2.1(c) following COP30, leaving the presidency needing to outline the future of finance initiatives in this area.

Always a contentious topic in the UNFCCC negotiations, finance lies at the heart of trust between developing and developed countries. The COP30 presidency therefore has a difficult task ahead of it to rebuild trust between Parties and make progress on the finance-focused areas of negotiation, while not letting this overshadow the broader COP agenda.

Conclusion